Current Milemarker

1

Day 0, A New Hike

Mile 0

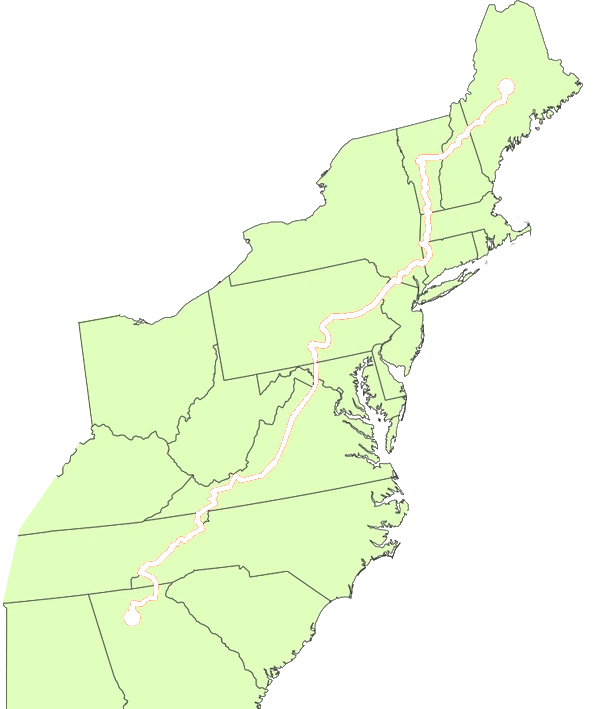

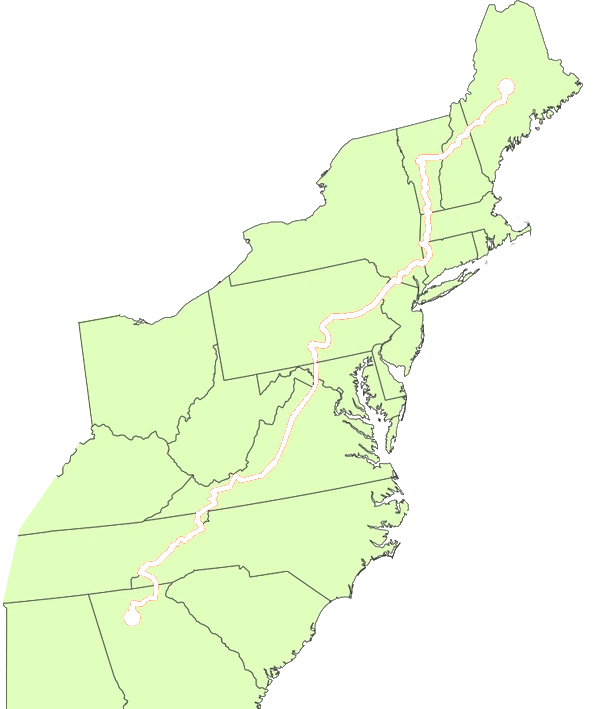

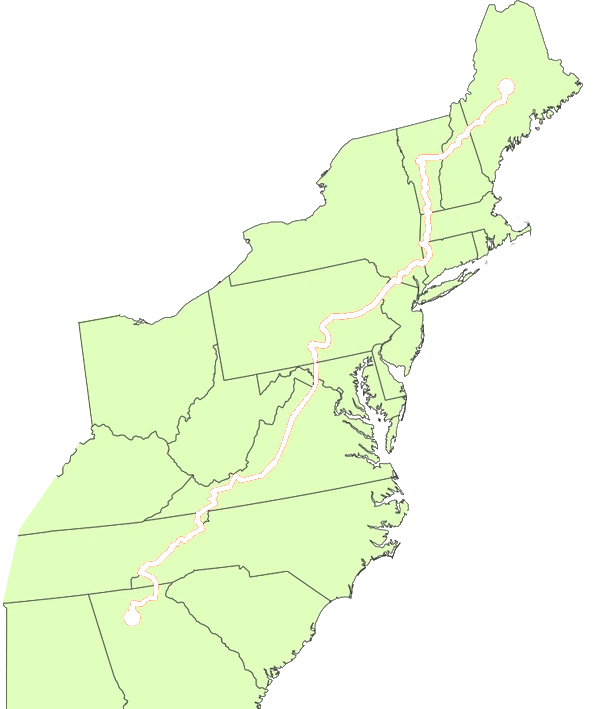

In 1921, the Appalachian Trail was conceived as a trail to connect the mountains of Eastern U.S. from Georgia to Maine. Exactly 100 years later, I'm going to attempt to walk the whole thing.

That's not the only interesting coincidence that the year 2021 brings up for me. Exactly 10 years ago, I attempted the same thing, in reverse.

Typically a Thru-Hike (completing a long distance trail in its entirety in less than one year) of the AT is done NOBO, or NOrthBOund. This is partially due to tradition, but for a few other reasons as well. Katahdin is the northernmost point of the AT, and is an incredibly difficult hike. The portion just South of Katahdin, called the 100 Mile Wilderness is the most remote spot on the whole trail. Naturally, Katahdin and the 100 Mile Wilderness serve as an incredible ending to the NOBO thru hike. It should also be mentioned that a typical Thru lasts from 4-6 months, and the fair weather follows the hiker a lot better when traveling NOBO instead of SOBO (SOuthBound).

The story of my thru hike attempt in 2011 is a short and scary one.

I was an inexperienced hiker, in my first year of college, taking the Summer to attempt to SOBO thru hike the AT. I knew almost nothing about distance hiking, camping, or anything really, that I hadn't read on forums online. The only important thing to me was to go on a grand adventure to break up the monotony of daily life. I felt constrained by the idea of the "ideal life" which included going to school, getting a good job, marrying young, and having kids. My heart yearned to do something unique and different, to reconcile the way I felt with the way I lived. I decided that I wanted to go SOBO, because my semester at University ended too late to go NOBO without facing serious snow in Maine by the time I arrived. Luckily for me, my grandparents have never wavered in their unbelievable support and belief in me. They offered to drive me all the way from Florida to Maine, to set me off on my adventure.

Arriving in Baxter State Park in Maine, I was elated to find good weather for my first day. Those of you who have experienced Katahdin know that it's an incredibly daunting experience for someone who has never summited a mountain. Katahdin is 5,269 feet tall, and absolutely towers over the surrounding landscape. Nearly all of Baxter State Park is in shadow as the peak dominates the surrounding forest. Some reports say that the Native Penobscot people of pre-colonial Maine avoided Katahdin, seeing it as the home of their god of storms, Pamola. None of that is lost on a visitor who plans to climb the mountain. I had no fear for the climb, but I should have had more respect for it.

Typically, Katahdin is hiked as a day-hike, which means you leave your heavy overnight pack at the base of the mountain, and hike up to the summit and back down with a temporary, smaller backpack. This is where the problems began for me. Being inexperienced, I followed the Park Ranger's instructions to a tee. I was told to hike up and back as quickly as possible, bring 2 liters of water, and to not go above the treeline if storm clouds were around. I packed my day bag with 2 liters of water, an easy lunch, a roll of toilet paper, and a couple other bits and ends. I didn't pack water purification. Katahdin is a hike that feels like 500 flights of stairs. With young knees, I had no real issues until I broke the treeline. Once you're up above the trees, Katahdin stars to throw a real challenge your way. It's basically a giant wall of boulders that you must scramble up (and eventually down) with no tree protection. There's a sheer drop to the left, a sheer drop to the right, and a sheer drop behind you for almost a mile of the ascent. Although there's not much "climbing" in the traditional sense of ropes and harnesses, there's quite a few spots where the only thing between you and certain death is a couple steel bolts, pushed into the boulder field to help hikers scramble up. The issue I faced was that I was running out of water. Trying to ration water was particularly difficult for me, because I was inexperienced enough to be tricked by "false summits". The shape of Katahdin's climb is such that a hiker may see only 10-15 boulders ahead of them, with clear sky ahead. If you don't know better, it looks like you're about to climb to the top of the ridge, for the last mile to be an easy, flattish trek to the summit. If you do know better, you know that once you climb that last boulder, another set of 10-15 boulders appear with another false summit on top. I knew nothing, so I kept drinking more and more water, thinking I was approaching the peak. By the time I ascended Katahdin, and took a picture of the Northern Terminus of the AT, I was out of water. Not only was I out of water, I was completely dehydrated. Climbing down the boulder fields just below the ridgeline was going to be impossible if I couldn't get a drink beforehand. In my pack I had a couple emergency Iodine purification tablets, given by another generous hiker I had passed earlier in the day. There was also a little trickle spring on the ridgeline, just before the big descent. Unfortunately, here's where I made the first of two critical mistakes.

The trickle spring was in a hole in the ground. I could get my lips to it, but my hard-sided Nalgene bottle was too big to fit into the crevice. There was no easy way to get the water into the bottle to be purified by the tablets. I was exhausted, and dehydrated. I drank directly from the spring. Feeling rejuvenated, I descended the boulder field, and faced no further issues that day. I did, however, make my second, even more critical mistake. During my descent of Katahdin, I drank another few liters of unfiltered water, thinking "I already drank it, why waste the time purifying it this time?"

Intelligent readers may make the obvious connection. Water at the peak of Katahdin, where no animals can live, is unlikely to be tainted. The only life up there is moss that serves as a natural filter to the water. Water in the raging waterfall and river halfway down the mountain does not have this protection. Little did I know, I was ingesting tainted, untreated water.

Being young, I felt great the next day, and set off to begin The Rest of the Hike. I had done the "hardest day" on the AT, and I felt excited and prepared for whatever may come. In reality, I would be neither excited nor prepared for the consequences of my actions.

I spent another 4-5 days hiking through the 100 Mile Wilderness when I started to become sick. Incredibly sick. Incredibly alone. Incredibly without cell signal. Every half mile I had to walk off trail to puke, or blow my nose. My nose was running at such a rate that I could barely breathe properly. At some point, I summited a small mountain, turned on my phone, and got some signal. It was around 40 degrees, wind blowing, and I could barely feel my fingers. I had to get out. I called my mom. I can't remember the detail of the call perfectly, but I was probably crying, probably saying how badly I had fucked up, probably begging for a mixture of help and forgiveness. My mother, being the most gracious and loving human alive, directed no shame towards me. She only gave me reassurance that she was going to get me out of there. Due to her diligence, and the help of a local hostel owner, I was taken out of the Wilderness, and delivered to Bangor, Maine. I was going home.

The flight connection I had took me to a major airport that I can only barely remember, which is where I discovered the seriousness of my illness. I ate one bite of food at the airport before immediately needing to run to the bathroom to expel it from my body. Over the next few weeks there was no amount of food that didn't provoke a violent reaction from one side or the other of my GI tract. I was suffering from a parasite called "Beaver Fever" but known to WebMD as Giardia. I could have died if I had stayed a couple more days on the trail. I lucked out, I experienced the reality of an adventure of this scope, and I had one of the most formative experiences of my young life, even if I had dramatically failed at my task.

I'm going back this year to right the wrong of 2011. Whether I fail or succeed this year is immaterial to that end. I want to go back out and give it another shot. I'm an experienced hiker now, and an experienced camper. If I fail again, whether it's injury, sickness, or just plain quitting, that's ok. I'm going to again have an incredibly formative experience and if I don't make it to Katahdin this year, maybe I'll be back in another 10 years to try again. But I intend to succeed.

I want to get to Maine.

I want to finish this story. I want to Thru Hike the Appalacian Trail.

Tomorrow I'm embarking on an adventure. This is not 1921, this is not 2011, this is 2021.

Tomorrow I will begin a story I will tell for the rest of my life.

Tomorrow I will begin A New Hike.